RETURNING TO THE ASHES OF KUUSAMO

“I remember when we came to Toranginaho, it was Christmas Eve and a beautiful moonlight. I saw that Kuusamo had become flattened. I said to the horse driver, “Where are we going to spend the night?”, and the old man said that we will find a place if we drive this sleigh road. We went from here via Neljäntienhaara. There was no one. It was completely empty, there were only chimneys standing and a cold wind was blowing. A reindeer herder had previously come to the outskirts of Nissinvaara, who had a warm shelter there, and we stayed there.” – Sulo Nissi.

The people of Kuusamo had been evacuated in the fall of 1944 when the war was coming to an end. The German troops retreating north burned most of the buildings in Kuusamo in September. Even telephone poles were blown up. After the Germans left, the Russian troops occupied the ashes of Kuusamo from September to November with the strength of 6 800 men and 846 horses.

When the first Kuusamo residents returned from evacuation to their home region in November 1944, there were only two buildings left in the parish village, Kuusela and Tyynelä in Lahdentaus. All that was left of the houses in the parish village were blackened ruins. The situation was a bit better in the remote villages. In the best case scenario, the residential building and cattle shelter had been spared from the fire.

At the end of 1944, mostly men returned to Kuusamo to investigate the extent of destruction and evaluate the families’ chances of returning to the home region. Most of the families couldn’t return to Kuusamo until spring 1945.

By the summer, more than 10 000 Kuusamo residents had already returned to their homes and reconstruction had begun. The women baked bread in the remains of the ovens, the children dug nails from the ruins and men worked on construction. A rebuilt Kuusamo rose from the ashes.

THE VILLAGES WITH 50-60 % DESTRUCTION RATE:

Heikkilä, Määttälänvaara, Soidinkumpu, Vasaraperä, Vuotunki

THE PARISH VILLAGE WAS DESTROYED ALMOST COMPLETELY

DURING THE LAPLAND WAR KUUSAMO LOST:

621 residential buildings, 526 livestock buildings, 1 022 other outbuildings, 21 municipal and parish buildings, 96 business buildings

In total 2 286 buildings

WAR DAMAGES IN TONS:

Rye 93, Barkey 776, Oat 25, Potato 1 368, Hay 5 054

LIVESTOCK BEFORE THE WAR 1944 / LOST:

Horse 876 / -, Cows 4 250 / 378, Bulls 53 / 49, Young cattle 873 / 375, Sheep 4 588 / all, Pigs 223 / all

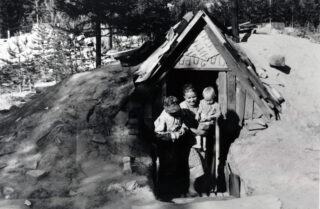

HOME IN A DUGOUT

Settlement of people returning from the evacuation to the destroyed Kuusamo was made a bit easier by the approx. 300 dugouts built by the occupying Russian forces. At best, about a hundred families lived in the dugouts in the parish village, approximately 600 – 800 people and hundreds of domestic animals.The dugouts were made habitable by building stoves in them, patching the gaps between the logs with moss and wallpapering the walls with newspaper. Sawn logs were used as benches and crepe paper was used as curtains in the windows. Many dugouts had dirt floors. The lighting came from candles and carbide lamps. Food was stored in wells. People tried to make living as comfortable as possible, but they still envied those who were able to live “above ground” in the temporary shelters, the so-called evacuation houses.

AUDIO running time 1:38 min (FIN only)

Crepe paper curtains and frozen potatoes

Listen to the story of a young bride from Kuusamo and her life in a dugout, in the city guide Atlas. The code takes you to the stories of Atla’s Kuusamo historical path.

PHOTOS BY AUKUSTI TUHKA

Kuusamo parish village in fall 1944.

By the door of a dugout home in summer 1945.

NAILS WITH BOOZE AND RUTHLESS SAWING

“The speculative trade got going at the very early stages of the reconstruction period. There was a dire shortage of iron nails. You could get a box of them with a bottle of booze from the scalpers. We had to get some strong booze from Oulu and use it to replace the nails necessary for the construction.” – Eino Vanttaja

Some men had returned to Kuusamo in the winter before the rest of the family to cut down and saw trees, which were then ready for the summer’s construction work.

The wood for the reconstruction of the parish village was first cut from Meskusvaara and then from the east side of Noukavaara, from where they were floated along the Meskusjoki river to the outskirts of the parish village to lake Leskelänjärvi.

The bang of the hammer and the sounds of the saws echoed in the destroyed Kuusamo night and day.

Roughly on the site of the current Nilo school in Nilonkangas, there was one shingle machine and saw. Five to six men worked on the machine making roof shingles for the houses in the parish village. The saw-owner Jani Nissi also had a Fordson Major tractor and a circular saw, with which he sawed reconstruction trees for different villages, such as Majavansuo, Oivanki and the school in Nissinvaara.

With the compensation money, you got six standards of boards, i.e. about 30 cubic metres of wood. There was a dire shortage of building materials. It was especially difficult to get windows and doors for the construction work.

People needed moss between the logs, shingle for the roofs, and stone and clay for the ovens. Unfinished buildings, old drying barns, etc. were demolished for wood material. The ovens of the burnt houses were dismantled and the stones were used for new ovens. In Kuusamo, the ovens were mostly made of slate and only the chimney and firewall were made of cement brick. In order to improve construction skills, the Talousseura of Oulu County organised training courses for bricklaying and construction work, among others.

“My father and I went to Meskusvaara with the horse. When the logging started I was 14 years old, but that winter I turned 15. I worked as a feller. Whenever I cut down a pine tree, it sank deep into the thick snow. It was quite a chore to cut branches from the trees in the snow. We didn’t take any food with us into the forest. Once we had to spend a few days eating only porridge. Nevertheless, we worked.” – Eino Jaakkola

FROM LOST KUUSAMO TO THE SHORES OF KITKA AND THE EDGES OF SWAMPS

The territorial cessions of Kuusamo resulted in more than 2 000 Kuusamo residents permanently losing their homes. A total of 151 new farms were established in Kuusamo to replace the lost 203 farms. In addition to these, 51 small farms and eight semi-immigrant farms were established.

The families in the ceded areas started rebuilding later than others, as they had to wait for replacement farms to be found. In addition to new buildings, the families also had to clear new fields.

Efforts were made to settle the residents of the ceded areas in village groups. Those who moved from Paanajärvi were placed around Lake Kitkajärvi, from Tavajärvi to Suininki, from Enojärvi to Heikkilä and from Kenttikylä to Kemilä. Also in the parish village, 29 cold farms were established on the edges of swamps, so that there were several farms in the same area to save costs. These formed small villages or village communities. Several villages of Kuusamo with -suo (‘swamp’) end suffix were born as a result of post-war resettlement, such as Syrjäsuo, Puurosuo, Hietasuo, Majavasuo, Teerisuo, Matosuo and Ruostesuo. Vaimojärvi village was also founded by the people of the ceded areas.

THE PATIENT PEOPLE OF KUUSAMO

Future Member of Parliament Niilo Ryhtä worked as a border region consultant and sent to the Oulu county government detailed information about the destruction in Kuusamo and what actions were required to fix them. In his reports, Ryhtä generally praised the patience of the people of Kuusamo and the composure in the face of various adversities and demanded swift action from the state in the promotion of construction works.

There was a shortage of builders and building materials, even the lack of horses was an issue. A large part of the region’s horses were especially used in the winter of 1945 – 46 to move cargo from Taivalkoski to Kuusamo, when the road could not be kept open for car traffic due to heavy snow. Consequently, there were not enough horses to pull the reconstruction trees from the forests to the lumber yards.

However, the reconstruction work progressed at the Kuusamo parish village and the majority of those who returned got to live in their new homes as early as 1948, albeit it did take a long time to finish everything.

THE EVACUATION HOUSE

Iivari Salmivaara built a small house out of logs of a drying barn, where the family lived from summer 1945 to autumn 1947, until the completion of their new home. In the summer season, you can visit this furnished evacuation house at the Kuusamo Museum. For more information about the evacuation house, see the city guide Atla.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE HIDDEN ITEMS?

Little Pirkko had made a discovery on the ground near the sauna, false teeth. With them in hand, she happily ran to the adults: “These are great new teeth for Aunt Lempi!” The child had heard talk that there was a need for such an item, but there was a shortage of everything. They were then taken to the parish village.

After returning from the evacuation, many were disappointed when searching for the items they had hidden. This is what happened at Aarne Säkkinen’s home. The furniture, clocks and other valuables were taken by horse to the barn in Matkajoki and hidden under the hay. These would have been needed when they started to live in a dugout by the river Meskusjoki, where a couple of the 25-30 dugouts that the Russians had built there were “seized” – for humans and animals. But there was nothing left. The barn was dismantled for dugout materials, the hay was fed to the Red Army horses and the furniture was taken across the border.

From the article Fall 1944 Part IV Meimi Mäntyniemi: There were dugouts behind the cemetery, Koillissanomat

BREAD AND CHICKENS

“The food was plain, and I remember that often after a meal, even though the stomach was full, the feeling of hunger still remained.” – Ulla Kaakinen (née Koskenniemi)

The German and Soviet troops had emptied the food cellars and eaten the sheep and reindeer that had stayed at home. In terms of food, people still had to rely on public welfare ration cards, substitutes and generosity. For example, in Lopotti in the parish village, near Kinnunen’s house, there was an oven left standing in Säkkinen’s place that the nearby residents used to bake buns and bread. The dough was baked on top of a detached door. Baked goods were also distributed to the neighbours.

During evacuation, many housewives had become familiar with caring for chickens and brought them and other new species of domestic animals with them to Kuusamo. To Soivionjärvi the first chickens came with the Manninen family, three chickens and one rooster, from which chicken farming spread to the neighbours as well. Store-bought eggs were hatched into chicks in a magpie’s nest. Anja Airisniemi (née Korva) brought three chickens, two male rabbits and flowers in a feed box. Lettuce and small field cucumbers grew in the vegetable garden left behind by the Germans, from which seedlings were distributed. Food aid came in the form of aid packages, especially from Sweden and the United States.

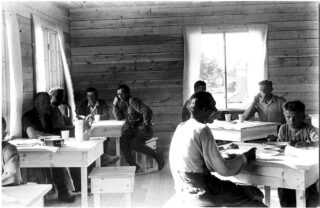

PHOTOS BY AUKUSTI TUHKA

Master Määttä, executive director of the economic society and municipal authorities of Kuusamo seeing the reconstruction activities in Alakitka in the summer of 1945.

Potatoes are put in the ground at Heikkilänniemi in the summer of 1942.

THE PARISH VILLAGE RISES

OFFICES AND SCHOOLS

The municipal offices got to move out of the Nilonkangas barracks first to a completed two-story building near the Co-operative store’s lot and finally to the actual municipal office, which was completed on the side of road Kitkantie, on the former border company’s plot. There was a lot of activity, for example in the school office. During the reconstruction period many children were born and by the end of the 1950s there were already 66 public schools in the municipality and an unprecedented large Nilo school in the parish village, where the public school, the grammar school and the intermediate school operated.

On the same plot as the municipal hall office building also rose the volunteer fire department with its workshop, garage and tower used to dry the fire hoses.

Next to the municipal hall was the two-story “Aravatalo”, where mostly municipal and state officials lived. The two-story building completed in 1952 must have been the first building in Kuusamo with the so-called modern amenities.

THE MUNICIPAL HOSPITAL AND THE PHARMACY

From 1921, the regional doctor Ali Ervasti had alone worked the position of a local doctor, and during the war also managed the military hospitals. When he returned to Kuusamo in the spring of 1945, doctor Ervasti got the Tyynelä house, which had been spared the destruction, to use as the family’s home and as reception rooms.

The hospital operated next door in the main building of the Kuusela house and Kuusamo’s first postwar pharmacy operated in the main living area in the house next to that. Pharmacist Veikko Vuorento moved with his family to Kuusamo in 1947. He built the new village pharmacy near the Neljäntiehaara crossroads. He also lived there with his family of five children.

In 1945, the regional hospital started its operation in two barracks next to the ruins of the parish village’s public school.

After a year, the regional hospital was moved into the children’s hospital located on the shore of Lake Torankijärvi, which was built during the Interim Peace and repaired into some sort of living condition in November 1946. Regional hospital -designation was abandoned after the war and the institution’s new name became the municipal hospital.

In 1952, a new hospital building was completed on the site of the former hospital on the shores of Lake Kuusamojärvi, as well as two doctor’s reception and residential buildings and an economic building. There were also separate wards like the communicable disease hospital located between the public school and the main building of Kuusamo Co-operative store, and the psychiatric ward that operated outside the parish village, in the Raatesalmi municipal home that was spared from the destruction.

FUNCTIONALISM AND BONES

The parish village’s school operated in several temporary premises until 1951. At first, a temporary barrack called Puukoulu (‘wood school’) was built on the site of the destroyed school. The Parakkikirkko (‘barrack church’), which was donated from Sweden and was used in many other places, and the Association of Peace’s pulpit also served as schools.

The white-plastered functionalist schoolyard of the public school rose impressively in the middle of the parish village. The two-story main building had a festive tower-like elevation, and the school’s gymnasium was the largest and most representative space in the entire parish village during the reconstruction period. There were also two teachers’ residential buildings in the open courtyard. The buildings were equipped with modern amenities including water pipes, drainage and electrification.

The main building still functions as a school, the second apartment building is used for living and the smaller building houses, among other things, the school museum.

When digging the foundations of the dormitory, human bones were found in the ground. Tönning, who led the construction work, has told about this special event as well:

“When we started digging the foundation pit for the house, we started to find many kinds of skeletons. There were men and women and children. We stopped the digging and asked the municipal authorities what to do now that the whole area is full of skeletons. We only received an instruction to put the bones in boxes and take them to the cemetery. The bodies had been inside birch tree bark and all had good teeth. Some even still had hair. When the number of bodies did not terrify our commissioners, we continued digging. Half of a body remained behind the wall of the sauna, but the shin bones made it to the cemetery.”

The bones came from the early days of Kuusamo’s first church located on the current site, from the turn of the 1600s-1700s. The so-called row burial was used when burying the poor of the congregation. The new public school also got the functionalist look characteristic of the era, which in the following decade was complemented by a new three-story concrete, white-plastered main building. The building, which contained a banquet hall, a weaving room, a sewing room, one classroom and living quarters for teachers and students, was put into use as early as 1953, partially unfinished.

VIDEO can be viewed in the cinema behind the curtains, run time 4:19 (FIN only)

The strong see and do – to Kuusamo’s rebuilders

What did the housewives grumble about the memorial?

Home district advisor Helena Palosaari explains in the video, among other things, what changes the artist professor Terho Sakki had to agree on in order to take into account the women of Kuusamo. The memorial is in front of the Kuusamo town hall.

The location of the monument and the video can also be found in the city guide Atla.

REBAR FROM THE BUNKER’S RUINS

Tauno Tönning, who was the foreman of several public buildings in Kuusamo, became aware of the endless lack of building materials. The inventive Tönning was responsible for, among other things, the contracts for the hospital building and the apartments for the border guards. The hospital was completed on the shore of Lake Kuusamojärvi in 1952.

“There was a severe shortage of nails and concrete steel, at least for us. I don’t know if it was due to lack of money. I solved the concrete steel problem with the help of captain Rantala. I heard that the russkies had blown up the dugouts near Kuusamo, and when they had spread, the concrete rebars in them had come out. I ordered a couple of hacksaws from Oulu and enough blades for them.

Then, on Sunday, I asked the border guard to borrow a car and I went with the warehouseman to the ruins of the bunker, and we sawed curly concrete bars to fill the car and took them to the construction site. The warehouseman and I straightened the steels and I reinforced the places to be reinforced with these steels. I straightened the steel with a sledgehammer, which I swung and the warehouseman rolled the steel on a plank. So the steel thing was arranged nicely and I informed our masters in Oulu that we don’t need steel, so you can keep it in Oulu. Otherwise, our work progressed well.”

Many kinds of things were also collected from the area of the Lahtela fortress in Salpa Line to be used as building materials for houses in the surrounding area. A piece of the field track could be bolted to reinforce the log walls of the houses.

THE GREAT PARTITION BLOCK

An important and possibly the biggest project in Kuusamo during the reconstruction period was the Great Partition. The forest lands of the municipality were divided into private ownership for the tenants, and the agricultural lands were allocated from the vicinity of the residential houses. The sale of wood started and cultivation became mechanised. Due to the Great Partition, the landless found paid work in the forests, sawmills and timber transport of the landowners.

The last and busiest phase of the Great Partition was during the reconstruction period from 1951. At that time, 33 Great Partition engineers, as well as surveyors, cartographers and other office staff arrived in Kuusamo. Field work also employed a lot of Kuusamo residents. Next to the municipal hall, the Great Partition house was completed, a two-story wooden reconstruction-era type house, where the project’s office work was largely done. Many Great Partition engineers and their families settled in Aravatalo house.

The two-story Kuusamo police building was also completed in the Great Partition block, where several local policemen moved to live. In the same building, there was a telephone centre, which grew rapidly towards the end of the reconstruction period, when telephones began to be purchased for private households. The arrival of new educated people in Kuusamo had many positive effects on the way of life in Kuusamo, especially on the invigoration of trade and cultural life.

THE SPEED OF CONSTRUCTION

The first three houses that went up in the parish village were the shoemaker Määttä’s house in Lopotti, the traveller’s home run by Kurki-Oskari, and the two-story building of the Co-operative store, which had a shop on the ground floor and apartments on the upper floor.

By 1949, 67 residential and livestock buildings and other necessary buildings had been built in Kuusamo, and in addition 75 farms were still unfinished. The remote villages were rebuilt first and the parish village last. While the other villages had been fully completed by 1950, the parish village still looked very deserted. The Kuusamo church was finally completed in the summer of 1951 and is generally considered a sign of the end of the reconstruction period.

PHOTO FROM KINNUNEN ARCHIVE

Ervastin Jyrävä’s houses Kitkantie 8 in 1948.

PHOTO BY AUKUSTI TUHKA

Construction workers in the Kuusamo reconstruction office’s canteen barrack in summer 1945.

THE SEED OF SAWMILL INDUSTRY

KUUSAMON KOVASIN OY / KUUSAMON JYRKKÄKOSKI OY

PHOTO FROM KUUSAMON KOVASIN OY ARCHIVE

Kuusamon Jyrkkäkoski sharpening stone factory milieu in Vuotunki in the 1920s.

The old builders and workers of the Jyrkänkoski sharpening stone factory returned to the destroyed Kuusamo in 1945. The feelings of sadness and anger produced by the complete destruction of the parish village were mixed with immense joy when the men arrived in Vuotunki. The surprise was great. The sharpening stone factory’s area was in good shape, even the light poles in the courtyard, which run on water electricity, were still standing, as if there had been no war. The seed of Kuusamo’s sawmill industry had been spared the ravages of the war and began to take root.

Due to the preservation of Kuusamo’s Jyrkänkoski sharpening stone factory, the factory was able to start up in just over a couple of weeks. The sharpening stones provided an income stream for reconstruction.

The demand for sawn timber was big. When the circular saw of the 1920s was found to be insufficient, Kovasin and the subsidiary Kuusamon Jyrkänkoski Oy expanded the factory into a sawmill. The factory received logs from the divisions and the municipality with special permits even before the completion of the Great Partition.

FROM A SHARPENING STONE FACTORY INTO A SAWMILL

Kuusamo’s industrialization had started in 1912, when Matti Eksymä founded Kuusamon Jyrkänkoski sharpening stone factory in Vuotunki. Kuusamon Kivitehdas Oy accelerated industrialization by mechanising and electrifying the stone grinding factory in the 1920s.

The factory’s turbine and stone machines were cast in concrete and there was electricity in the area and a telephone and radio in the office building. The milieu of Kuusamo’s sharpening stone factory lived in its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s.

The first frame saw powered by water electricity was built at the Jyrkänkoski factory in 1949. The Jyrkänkoski factory milieu experienced a period of great employment between 1945 and 1960. All the locals got to work and sawmill installers and truck drivers had to be hired from other parts of Finland.

With the permission of the president, Tenho Moilanen got a driver’s licence as a minor, when there was such a severe shortage of car drivers. The timber was taken to Oulu with the factory’s own trucks to be loaded onto ships. Log sellers also bought sawn timber and planed the boards to be used as decoration material. Among the biggest buyers of timber were the municipalities of Kuusamo and Taivalkoski, the Kainuu Border Guard, electricity companies and, the biggest of all, Imatran Voima and the Myllykoski power plant.

LIVELY IRONWORKS

By the 1950s, the demand for sharpening stones had waned due to the mechanisation of agriculture, and their production and export to Europe stopped. On the other hand, the demand for lumber was so strong that three frame saws were used up in ten years. The factory was left unrenovated when the partners could not find common future prospects. Jyrkänkoski had developed its own lively ironworks. The wood saw and planer and the mill worked in different factory halls in several shifts. Kauppinen, a coal burner, produced coal in Saunaniemi as an independent entrepreneur and sold it to Kuusamon Kovasin.

There was also a representative sauna in Saunaniemi. At the intersection of Paanajärvi and Tavajärvi roads, there were two shops, Otso and Co-operative Store, and across the river there was a Co-operative. In addition, Määttälä and Vuotunki had their own shops.

Kovasin’s partners Johan Vilhelm Määttä and Antti Armas Määttä founded Kuusamon Saha Oy/ Vuotunki Oy on the neighboring plot. There was enough wood for the needs of their own village and municipality, but large quantities were also exported abroad.

Until the summer of 1968, Jyrkänkoski Oy sawed supplementary batches for the export of the Vuotunki sawmill. Gradually, a planer and a storage area were built in connection with the sawmill, from where the timber was driven by truck to Oulu to be shipped. Vuotunki Oy ran several shifts during the summer and employed people from nearby villages.

Kuusamon Osuusmeijeri bought the shares of Vuotunki Oy in 1974 and continued sawing and planing until 1982. Osuusmeijeri sold the sawmill area to Rajanuorunen Oy, which left it bankrupt after plans for a tourist area in Nuorunen on the Russian side fell through.

PÖLKKI BROTHERS

The Pölkki brothers, who moved from Kyyjärvi to Posio in 1939, sawed railway ties for the Germans for the construction of the Hyrynsalmi-Kuusamo Line with a field saw during the war years 1942–1944. After evacuation the Pölkki returned to Kuusamo and started sawing in the parish village. At the end of 1949, the Pölkki built a steam sawmill and residential houses in Kolvankijokisuu in Lahdentaus. Bernhard Pölkki’s house remains from the sawmill area. The Pölkki sold the sawmill in 1954, built a new sawmill in Junttilanniemi, but stopped due to the difficult supply of timber which made the business unprofitable.

KUUSAMON PUU

The new owners opened foreign trade to Great Britain as Kuusamon Puu Oy. The sawmill burned down except for the planer in 1965 and the company was transferred to the ownership of Johan Vilhelm Määtä. After the Virranniemi sawmill was built in the centre of Kuusamo, Määttä built a new sawmill in Taivalkoski and took the European export customers to the Taivalkoski sawmill. Kuusamon Puu Oy was declared bankrupt in 1984. J. V. Määttä passed away in 1986. He had managed half a century at the head of the stone and wood industry in Koillismaa.

PHOTO FROM KUUSAMON KOVASIN OY/MOILANEN ARCHIVE

The finished lumber was loaded in front of the Jyrkänkoski factory into the factory’s own trucks.

Sylvi Kantola née Moilanen was the note takes, CEO Johan Vilhelm Määttä on top of the load, Sulo Määttä (Porvari) was the driver, and Urpo Määttä and Eevi Härkönen (Rontti) were the loaders.

PHOTO BY JUHANI KINNUNEN

The Lahdentaus steam sawmill built by the Pölkki brothers in 1949-1950 was part of the parish village landscape.

PÖLKKY

Erkki Virranniemi and his family had started sawing operations in 1965 at an Ari machine circular sawmill in Kantojoki. The company started as Virranniemen Saha Oy. For the new sawmill, a plot of land near the centre of Kuusamo had been acquired along National Road 5.

The first name Virranniemi Oy did not go through in the trade register. The company’s final name was Pölkky Oy. The company started its actual operations in 1969. Pölkky bought Oulun Rakennuspuu Oy in 1983 and the Taivalkoski sawmill in 1997. Kitka Wood was taken over by Pölkky Oy in 2009, the UPM Timber sawmill in 2012 and the Kajaani production plant in 2013. The last turning point in the wood sawing industry of Kuusamo and this northern region happened when the Austrian family company Pfeifer Oy Group bought all of Pölkky’s operations at the turn of the year 2022-2023.

KURTTI SAWMILL

The story of Kurtti sawmill in Käylä began in the 1950s when three brothers were sawing timber on their own property in Kurtinvaara. Later in 1960, they built a sawmill in Käylä. After mining explorations began in Kuusamo, Kurtti brothers sold the area and buildings they owned to a mining company.