Vuotunki was the northernmost corner of Maanselkä’s siida.

The village has a very strong Sámi past. 1-2 families from the siida of Maanselkä have fished in its lakes in spring, summer, and autumn. The name of the village suggests that the Sámi of Maanselkä practiced vigorous hunting in the area: vuottuu means that you can see the tracks of an animal.

The Vuotunki area consists of an old, village-like settlement formed around Lake Vuotunkijärvi, the independent village of Suorajärvi, the Paljakka settlement along the road to the border, the settlement along the Vapavaara road, where the population from the ceded areas has been resettled as a result of settlement operations, and the Kuntijärvi settlement along the road to the border.

Vuotunki belonged to Heikkilä village for a long time, and it became its own Suininki village in 1846.

The area has been inhabited by people practicing gathering economy since ancient times, since the Stone Age. Based on scattered findings, e.g., Kuusinkijoki’s Laherma, Ala-Vuotunki’s Korpela and Ketola and Taivalharju have been at least temporarily inhabited since prehistoric times.

Until the 16th century, only the Sámi lived permanently in Kuusamo. There were two siida in the area, Maanselkä and Kitka. The Sámi were nomads who had some reindeer as draft animals and decoys for deer hunting. They lived mainly by fishing and hunting deer and other game, no one had big reindeer herds. In the summer, they were spread out in the lake areas, each in the vicinity of their own fishing spots. For the winter, they gathered in winter villages, of which there were two, one between Taliskotalampi and Muovaara and the other in Yli-Kitka.

The first settlers of of Kuusamo have come to the west side of Maanselkä and then to the region of Kuusamojärvi and Kitka. They came in the early 1680s, cut trees for slash-and-burn cultivation and made simple houses and saunas on top of the hills. The last Sámi resident in the village was Lauri Heikinpoika Oikari.

At the courthouse in Kemi in 1686, vicar Cajanus asked for a permit for Olli Pohjalainen and Antti Määttä from Sotkamo to settle in Vuotunki.

In the photo, Valma Lämsä Master of Arts, nonfiction writer, visual and media artist, and Eino Hanhela. Eino Hanhela, 91 years old, has been making whetstones at Kuusamon Kivi Oy in the 1930s–1940s, while his father Eetu Hanhela was working as a foreman in Jyrkänkoski. Sharpening the scythe has been a part of his life until the last few days.

Jyrkänkoski whetstone factory

“Has Kuusamo had a good whetstone year?”

Whetstones were made by hand in Kuusamo from the 18th century. First in Kitka, then in the village of Heikkilä and in many places in the villages left behind the border, from where the necessary materials, slates, were initially brought. A household could produce 6 000 whetstones per year, which were either sold to middlemen or taken all the way to the market in Oulu. There was a familiar saying in the market: the familiar buzz: “Has Kuusamo had a good whetstone year?”

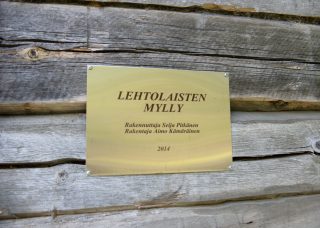

Kuusamon Kivihiomo was founded in 1912 by Matti Hermanni Eksymä in Kuusamo’s Heikkilä village, today’s Vuotunki. At Jyrkänkoski, Suininki’s waters flow all the way via Varisjoki to Lake Vuotunkijärvi.

Laajusvaara slate was also the raw material for the floor stones of our parliament building; they were polished at Jyrkänkoski. The Turkish sultan sharpened his dagger with a whetstone from Kuusamo.